Preventing Women from Working: A Family and Economic Crisis

Preventing women from working is not only a “freedoms” issue; it is an issue of economics, livelihoods, and family stability. A decision that excludes half of society from production weakens everyone—men, women, and children—and turns the family from a life project into a daily battle against poverty.

Let us think about this in a simple way, through examples close to reality.

Example One: A Family Dependent on One Person

Imagine a family made up of a father, a mother, and six daughters.

The first question is obvious: who is responsible for this family’s income?

In a society that prevents women from working or restricts them, the answer is usually: the father alone.

Now let us use roughly realistic numbers:

How much does a large family like this need to live each month?

Let us say: $500 as a minimum for food and basic necessities.

So how much must the father earn so the family does not collapse?

At least $700, because anything less places the family on the edge of poverty, under constant pressure, and exposed to hunger or severe deprivation. Life does not stop at food; there is rent, medical care, education, clothing, bills, emergencies—and crises do not ask permission.

But what if the father earns less than $100?

At that point, the situation becomes so harsh and painful that the family falls into extreme poverty, and life turns into forced austerity that leaves no space for dignity or stability.

Now let us ask the question that clarifies the entire idea:

What if the father earns $100, but every capable person in the family also earns $100?

In that case, the family’s life would change completely. Income would no longer be confined to one person carrying everyone’s burden. The family would be able to cover its needs, move from poverty to a decent standard of living, and over time perhaps reach a far better level. This is not a dream; it is an economic rule: increasing the number of earners strengthens the family, reduces risk, and opens opportunities for progress.

The difference between the two situations is not about “morality” or “intention,” but about one thing:

Did we allow every capable person to work and contribute, or did we lock half the family into the role of consumption only?

Example Two: The Farm That Collapses Because of One Decision

Let us move to another example that is even clearer.

Imagine you have a farm that needs 15 workers to operate properly. On this farm, 20 people live and eat from its produce. If you distribute tasks wisely, you will achieve good production. Perhaps five individuals may not have a direct role, but you can easily assign supporting tasks: transport, organising, follow-up, marketing, maintaining equipment, and so on. The farm grows and develops quickly because every person becomes part of the production cycle.

Now imagine a different scenario:

You decide to prevent half of the people from working on the grounds that they are women and therefore have no right to work.

What will happen?

You will have only 10 people working instead of 20, and they will be expected to run a farm that actually needs 15 workers. The result is predictable:

- They will work with double effort.

- They will burn out quickly.

- They will spend their income supporting a large number of consumers who were prevented from producing.

- There will be vacant roles that no one fills—not because people do not exist, but because they are “forbidden.”

- Half of the community will be turned into forced consumers, not because they are incapable, but because the system chose to disable them.

At that point, the farm becomes threatened with collapse—not because of a lack of land or water, but because of a social decision that kills productivity and manufactures incapacity with its own hands. Over time profits decline, the ability to develop weakens, pressures accumulate, and the workers become exhausted people without a decent life. In the end, the family deteriorates, the land is drained, and the future is lost.

This is exactly what happens in countries that prevent women from working. It is like a farm that disables half its workforce and then expects to flourish.

Preventing Women from Working: Officially Producing Poverty

When a woman is prevented from working, you are not “protecting the family” as some claim—you are weakening it. You make the man alone responsible for heavy burdens he may not be able to carry, and you deny the family a source of income that could have transformed its life. More dangerously, you make the entire society fragile in the face of crises: any illness of the father, any job loss, any price surge, any war, any emergency—can bring down a whole family because it has no alternative sources of support.

But when women work, earn, and contribute, the family becomes stronger and more able to absorb shocks, closer to stability, more capable of educating children, improving health, and building a better future.

Conclusion: Women’s Work Is Not Secondary—It Is a for Progress

Women’s work is not a luxury, nor a superficial issue. It is a fundamental factor in the advancement of societies and the flourishing of civilisations. It is a direct way to reduce pressure on families, improve income, expand opportunities for education and healthcare, and build a more balanced and stable society.

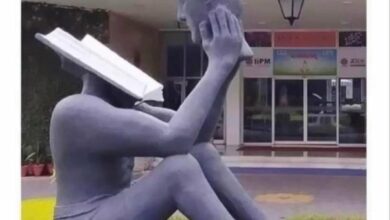

A society that prevents women from working is like someone who cuts a bird’s wing and then demands that it fly.

No country can truly progress while disabling half of its human potential.